Mega investors, crypto and tech bros: Why Vance and Harris’s San Francisco ties hold the key to the election

The candidates, ideas, and vibes of this election are deeply tied to the San Francisco Bay Area. What does this tell us about how the election will shake out? Io Dodds and Josh Marcus report from the 2024 election’s unlikely power center

Last week, at a speech in Florida, Donald Trump warned that a Kamala Harris presidency would “forcibly impose crazy San Francisco liberal values on Americans nationwide.”

San Francisco, population 808,437, has long been a punching bag for conservatives nationwide — but Trump neglected to mention that his own running mate, JD Vance, also has deep ties there.

Perhaps more than any other time in US history, both sides of the ticket include people with fundamental ties to the Bay Area.

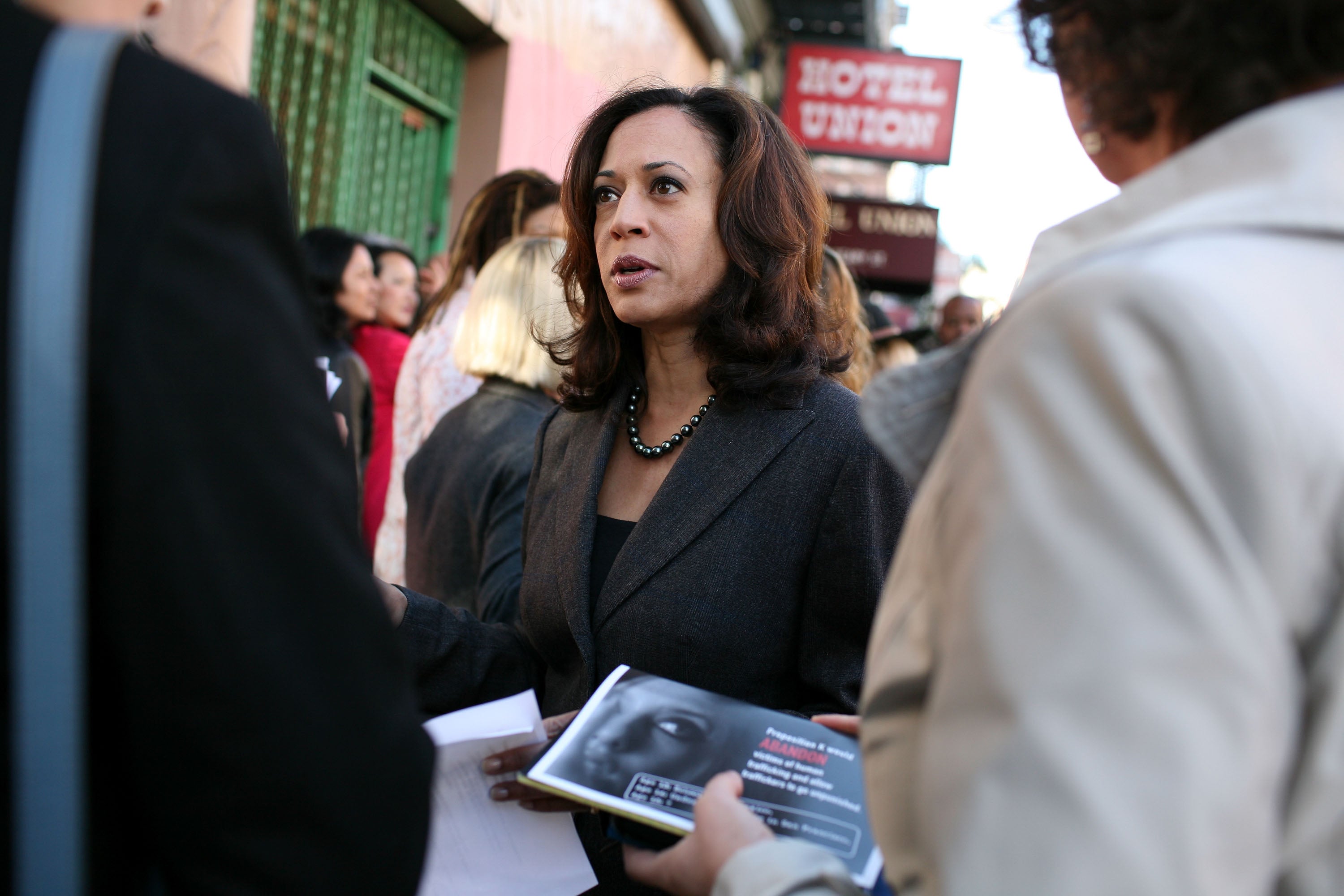

First, there’s Vice President Harris. This week she became the first Californian Democrat to secure the presidential nomination. Growing up in Oakland and Berkeley, she methodically rose through local and then state politics, bridging the region’s long activist tradition and its old-school local Democratic machine.

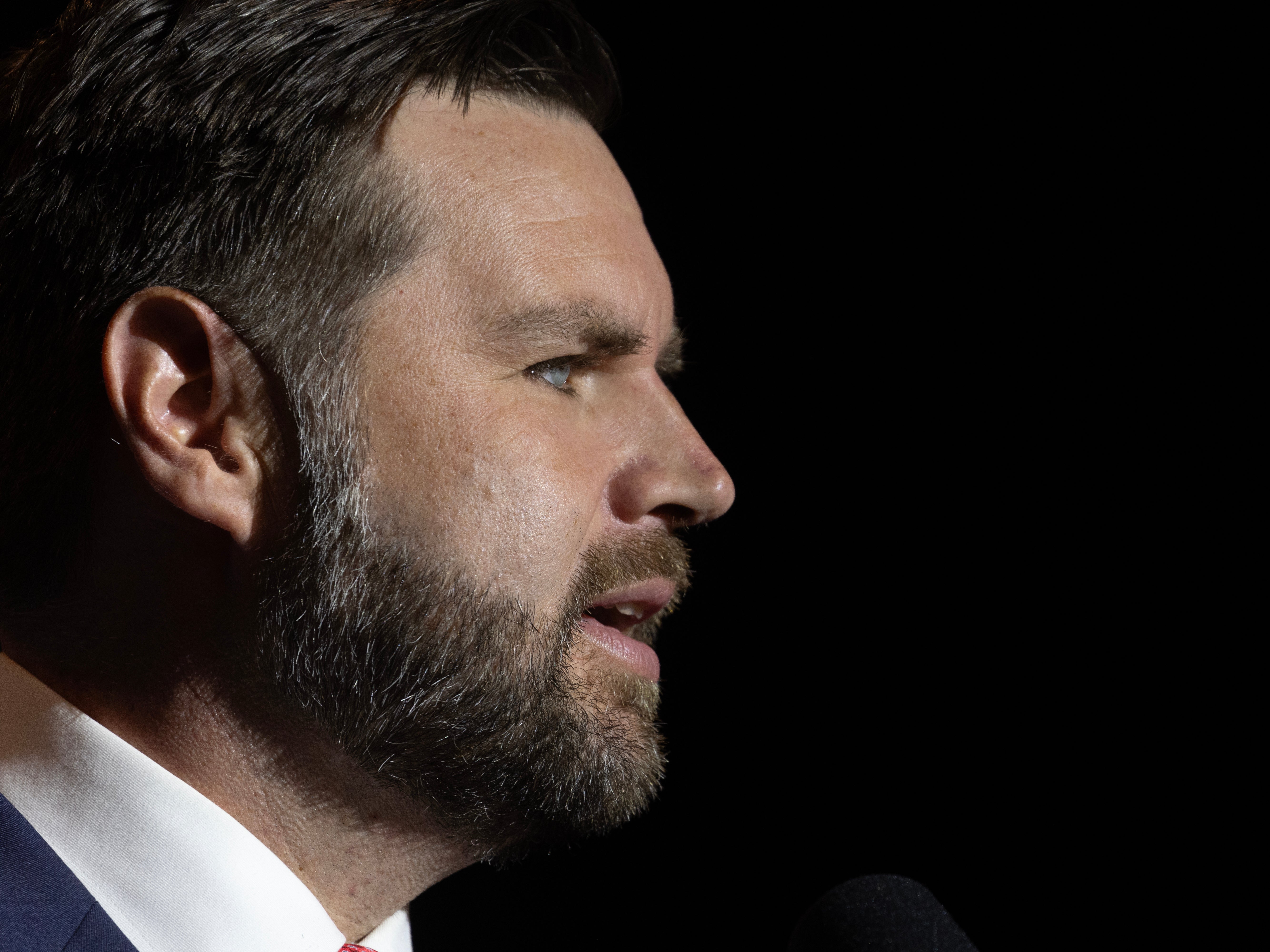

Then there’s Ohio senator and vice presidential candidate Vance, who spent years as a Silicon Valley venture capitalist alongside conservative investor Peter Thiel. The Facebook backer not only shaped Vance’s ideas but supported his senate campaign, reportedly introduced him to Trump, and – along with other right-leaning tech barons – helped persuade the former president to put him on the 2024 ticket.

This race probably wouldn’t even be Harris versus Trump were it not for another San Francisco legend, former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who reportedly was instrumental in getting Joe Biden out.

Meanwhile, Trump has begun making aggressive overtures to the cryptocurrency industry that boasts so many Bay Area devotees.

So how did one relatively small city – not even California’s biggest – gain so much sway over national politics? And what does that foreshadow about the 2024 election?

The contest between Harris and Vance is in part a duel between two California power blocs, with a tangled history of battle in a city that’s always had its share of big dreamers, from its roots in the Gold Rush onward on through the tech revolution.

San Francisco is a “petri dish for bright, adventurous people," according to Bay Area real estate developer Mark Buell, a Democratic donor who served as one of Harris’s earliest political patrons.

“It produces interesting people who will succeed,” he tells The Independent.

‘A knife fight in a phone booth’

Harris’s parents were Marxist academics from India and Jamaica, who met at the University of California Berkeley during the flourishing of the civil rights movement, the Black Panthers (which began in Oakland), and the Third World Liberation Front. They took their young daughter to protests in a stroller.

Harris went about her politics in a different way, seeking to make change from the inside as a prosecutor in Oakland and then San Francisco.

Not everyone appreciates that. According to Cat Brooks, a longtime Oakland racial justice advocate and co-founder of the Anti-Police Terror Project, Harris long ago chose the establishment route, trading access for constraints within the upper echelons of power, committing to a much less radical vision than Harris’s parents’ generation.

“Black folks in this country make decisions in terms of how they want to see change," Brooks, who is mixed-race, tells The Independent. “She chose to be part of a system that incarcerated more people, and certainly more Black people, than any other part of the planet.”

By 2002, Harris had set her sights on being San Francisco DA. Getting there meant running a gauntlet of old money donors, political operators, and activist groups.

When Harris and Buell had lunch together in 2002 to discuss her campaign, he was skeptical. Though she was good friends with his stepdaughter, he thought of her as a "socialite with a law degree". By the time the lunch was over, he’d agreed to back her and chair her fundraising committee. Together they raised $100,000 by the end of the year – an impressive amount in those days.

"Kamala is such a phenomenon," Buell says. "She would never have won had we not been able to raise a vast amount of money to get her name recognition. [But] then her own talents took over."

Insiders describe the city as one of the most competitive political environments in the US, like a state capitol anywhere else, even though many of the candidates share liberal ideas.

"If you’ve come up in San Francisco politics, by the time you get to Sacramento it’s as if you’ve been playing AAA baseball, and you’re sitting next to a guy who’s barely out of the rookie leagues,” Dale Carlson, a veteran San Francisco lobbyist and PR consultant, tells The Independent.

Carlson’s wife Meaghan Levitan, for instance, had to beat out 41 candidates to get elected to the Democratic Party’s central committee in 1998.

"If you want it in San Francisco, you have to work hard for it," Levitan says.

Sam Lauter, a lobbyist and fifth generation San Franciscan who advised Harris during her DA campaign, describes city politics as "a knife fight in a phone booth,” with attacks that are often "nastier than you would think" given that many rivals are fairly close together on the liberal spectrum.

Harris, by all accounts, played the game immaculately. She was a protege of legendary San Francisco mayor Willie Brown. She quickly became a fixture among the city’s limousine liberals, socializing — and fundraising — with local dynasties like the Gettys and the Fishers, the founders of the Gap clothing brand.

At one point Harris dated Brown, who appointed her to two government boards when he was in state politics. People who knew her back then are divided on how much he helped her, but the relationship didn’t last long and Harris’s rise never stopped.

In 2004 she became San Francisco DA, the first person of color to do so. There, she won plaudits for Back on Track, a program allowing first-time drug offenders to vacate their convictions after completing a series of social service programs. Others criticized her tough on crime tactics, including a program, later copied statewide, prosecuting the parents whose children chronically missed class. The policy ended up often targeting poor parents of color.

It’s the same kind of progressivism-lite the Biden-Harris administration showed after the 2020 murder of George Floyd. The administration vocally supported police reform and met with the Floyds, but failed to pass the Justice in Policing Act. They supported proposals for spending millions hiring new officers, despite progressive calls to defund the police. Defund, as it happens, has been a priority for Oakland activists dating back the 2009 killing of Oscar Grant, and even in a sense to the Black Panthers, but Harris had long since left the protest movement.

All of this provides important clues about how Harris will campaign in 2024 and may govern after that. For all Trump’s efforts to paint her as a beret-wearing socialist, when the San Francisco Chronicle endorsed Harris for DA in 2003, its headline was "Harris, for Law and Order."

The Republican side will surely dispute that framing. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, while battling Trump for the nomination, regularly claimed San Francisco was an emblem of Democratic lawlessness. He visited the city as a PR stunt and at one point held up a “poop map” of San Francisco during the strange, quasi-presidential debate he had last year against Newsom, himself a former mayor of the city.

Trump, meanwhile, has recently been speaking apocalyptically about the “plunder, rape, and slaughter” of American cities, claiming in the last 15 years, San Francisco went from “the best city” to “barely liveable.”

Harris, in turn, hasn’t been afraid to bust out some San Francisco-style jabs at her opponents, comparing Trump to the "predators… fraudsters… and cheaters" that she once put behind bars, and ridiculing her GOP rivals as "weird", a far cry from the magnanimous Obama style or Joe Biden’s throwback bipartisanship.

‘They see Vance as one of their own’

Vance came up through an entirely different Bay Area political scene: a deeply online wing of the tech culture that defies outsiders’ understandings of the Bay Area as a diverse, liberal stronghold.

Until recently, there was a social compact about Big Tech’s place in national politics, according to tech journalist Jacob Silverman, who is writing a book on Silicon Valley’s rightward tilt.

Founders would make a fortune, do some charity, and would be celebrated as economic heroes, while avoiding scrutiny from the public or public regulators. Much of Big Tech’s money went to Hillary Clinton in 2016.

“That has broken down in a way they find unfair,” Silverman tells The Independent, pointing to rising tech criticism and antitrust advocates like Lina Khan, chair of the Federal Trade Commission.

A similar social bargain played out, then flamed out, locally. As recently as 2011, San Francisco offered a "Twitter tax break" to lure big companies to a troubled downtown neighborhood. But the tech boom brought intense gentrification and displacement of poorer San Franciscans, who now had to compete over a stagnant housing supply with coders making six figures. Private buses ferrying tech workers became a common (and much-resented) sight. Many blamed Big Tech for San Francisco becoming a place of diverging fortunes, of billionaires and pervasive homelessness.

Even before this techlash, Vance’s billionaire mentor Thiel was the most outspokenly right-wing of Silicon Valley’s kingmakers. He wrote a book criticizing multiculturalism and in 2009 famously declared that he didn’t believe “freedom and democracy are compatible.”

Since then, the PayPal co-founder donated to support Trump in 2016 and funded conservative candidates’ senate campaigns. One of Thiel’s companies, Palantir, provided digital tools to Immigration and Customs Enforcement during the Trump administration’s migrant crackdowns – a reminder of Silicon Valley’s increasing, oftentimes internally controversial, connection to defense.

Thiel’s right-wing ethos dovetailed with the tech elites’ growing discontent over San Francisco itself. Elon Musk regularly (and inaccurately) trashes the city as a hellscape of soaring crime, and has moved to sever his ties with the Bay in favor of Texas. Money from tech and business interests fuelled the recall of progressive San Francisco DA Chesa Boudin, who sued to classify drivers for DoorDash, headquartered in San Francisco, as employees rather than gig workers.

From one tech perspective, the San Francisco machine that forged Harris amounts to a bunch of back-slapping progressive apparatchiks blaming Silicon Valley for their own negligence while failing to solve big problems.

The Trump-Vance campaign, supported by tech heavyweights Marc Andreessen, Ben Horowitz, and Musk, could not have arrived at a better time to capitalize on these dynamics. Even Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, whose platform once banned Trump over his role in the January 6 riot, recently deemed the former president a “badass” for surviving the assassination attempt.

“For a lot of these VCs and stuff, they see him as one of their own,” Silverman says. “They see a capitalist who thinks like them, that’s very pro-tech, anti-regulation in general, and is going to laud them as visionaries and let them do what they want.”

The identification goes beyond just a pro-tech stance. Vance swims in the same conspiratorial waters online as figures like Musk, who is increasingly committed to the claims of the racist Great Replacement Theory, even though he denies subscribing to it.

Vance, like Musk, is a natalist. He follows white nationalists and conspiracy theorists on social media and accuses single women and the “childless left” of being part of a “civilizational crisis” of declining birth rates. He’s also an investor in Rumble, the alternative video platform that’s rife with hateful content.

Vance’s and Harris’s circles appear to have almost never overlapped, yet in a strange way, both politicians represent different sides of the same coin.

"We are a city primarily of transplants,” concludes Levitan. “People come to the city, they fall madly in love with it, and they want to be a part of it."

In the 1840s and 1850s, it was gold that brought all manner of adventurers and profiteers to San Francisco. Later, there was immigration from China and Japan; then a Black exodus from the American South, and an LGBT+ one from the rest of the country; then came devotees of the late ‘60s counterculture, hoping for political revolution or a higher consciousness.

Mix all that together and you end up with a population that is unusually passionate, open to new ideas, and committed to fighting for them. In November, we will find out which version of the San Francisco dream wins more votes nationwide.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments